Planning urban environments is a long-term process. The future under debate does not exist yet, we have merely plans, visualisations and simulations of it. These are not necessarily easy to understand without a pre-existing knowledge base, posing a challenge for multi-disciplinary co-design and public participation—essential parts of the planning process.

Grasping the current situation is not without a problem either, as a multitude of unseen factors affect the urban space and its development. While some of these currently remain unknown unknowns, others can be tackled by inviting the right expertise to the planning process. As urban planning extends to a more diverse community, better communication tools are needed to facilitate knowledge exchange and help all parties understand the topics and proposals the same way.

The Augmented Urbans project has explored ways for extended reality (XR) technologies to support integrated urban planning. The question for the project has been: how can technologies bring new knowledge resources and stakeholder groups to the planning process. Only relatively few applications and trials have been created in this field. The current project has developed and tested twelve XR tools in seven Central Baltic cities and municipalities within this project. This article presents practice-based insights collected throughout the project; from its reports, workshop discussions and presentations by the partner urban planners and other experts.

Online, offline or on-site interaction?

The range of XR tools and applications is broad; different channels with distinct affordances and limitations can communicate the same content. The key in deciding XR tools is to select by identifying the need or needs within the planning process and understanding who and where will be using the XR tool.

The benefits of communicating online is not limited by time or place and thus affords a large number of potential participants. For example, the municipality of Viimsi shares the main points of the Haabneeme Master Plan together with thematic maps and explanatory texts online to provide locals with a quick overview of the proposed development.

Going online, however, limits the technological options as more immersive solutions often require specific equipment not yet readily available at homes or workplaces. The question is more about the aspired user experience and level of immersion than the contents. The 3D contents created for a virtual reality experience, for example, can also be streamed online and viewed on a web browser facilitated by an external cloud server such as Furioos, as was done in Stockholm in order to share the interactive prototype of UrbanSphere.

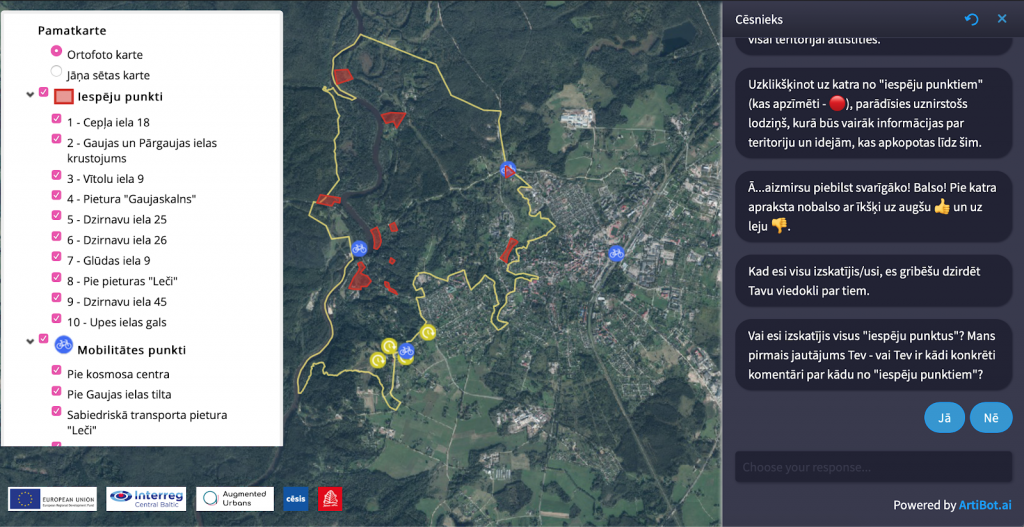

Regardless of the platform, receiving stakeholder inputs relevant for the planning process is crucial. To facilitate this with a mass of participants, the online portal developed in the town of Cēsis includes a chatbot to guide citizens in giving feedback.

The urban planners within Augmented Urbans agree that technology does not replace traditional public engagement methods, rather, it opens up new opportunities to expand them. The project has proven that organising on-site pop-ups facilitated both face-to-face discussions and created a venue for using XR tools that require specific equipment and guidance. Although such public involvement methods take more working hours from planners during events and the number of participants is limited compared to online solutions, they offer a forum for more in-depth consultations. Based on experiences during the project, a touchscreen seems to be a simple enough interface to use during events that people are able to explore and discuss the plans. Many of the online tools function well also on a touchscreen.

Mobile applications, in turn, can communicate location-based information and allow viewing the plans on-site. These require uploading and installing an app, creating a threshold for participation. Still, it is a valuable tool as it provides a real-life experience of the site.

An easy first step with 360° to encapsulate the spatial experience of the planning site

As a medium, 360° captures the view in all directions from any selected spot. It offers an easy but also relatively cost-effective way to capture the current situation on-site. Viewing 360° footage with a VR headset allows an immersive experience, and it is also possible to view it on-screen without any special equipment. Several existing online platforms such as YouTube and Facebook already support 360°, in addition to many other platforms specifically dedicated to 360° contents.

(photo: Päivi Keränen)

In practice, 360° material allows virtual visits to the planning site to convey the spatial experience of its key spots e. g. in participatory stakeholder workshops or planning meetings. Even a large and spatially diverse planning site can be covered fast with virtual visits, making them a useful tool for planners. Re-capturing the site over time allows following up on the rhythms of the place such as the temporal changes of seasons, times of day, and how the urban structure develops.

Without an accompanying map or other guidance to provide context, 360° can seem fragmented with no evident connections and distances between the filmed clips. Complementary information can also be added within the media content as voice-overs or additional graphics to point out e. g. citizen experiences of the space, historical notes, future scenarios, identified planning challenges, or currently open questions to focus the attention.

The 360° video format enhances the immersive experience by capturing the movement and soundscape of the site. In test sessions conducted in Gävle, the participating planning professionals found this a significant added value of using 360° as a tool within the urban design process. On the other hand, the smaller file size of 360° photographs makes them more convenient to share online. In addition, the photos allow better image quality with higher resolution.

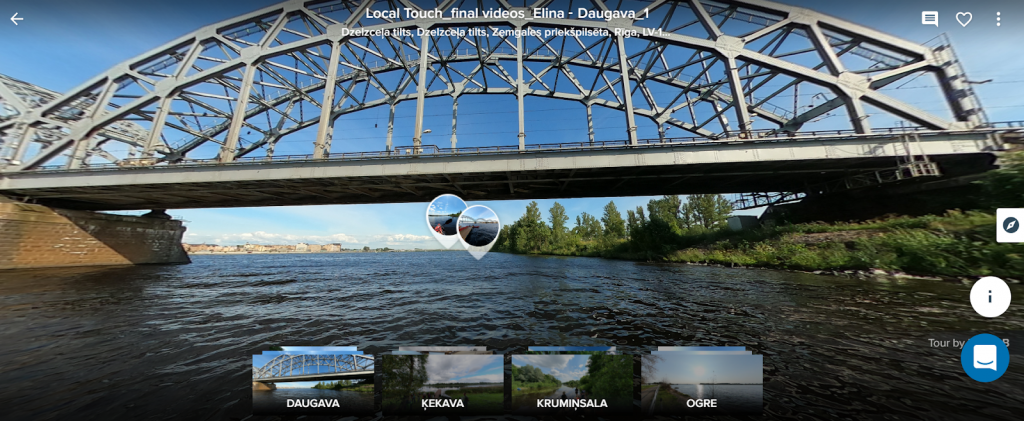

Several Augmented Urbans municipalities used online 360° material to communicate the current state of the environment, future plans, spark ideas of potential use for the site, or give information about previous participation results. For example, the Riga Planning Region team documented the case sites along the Daugava River with 360° snapshots and made them accessible to local stakeholders via the online RoundMe platform.

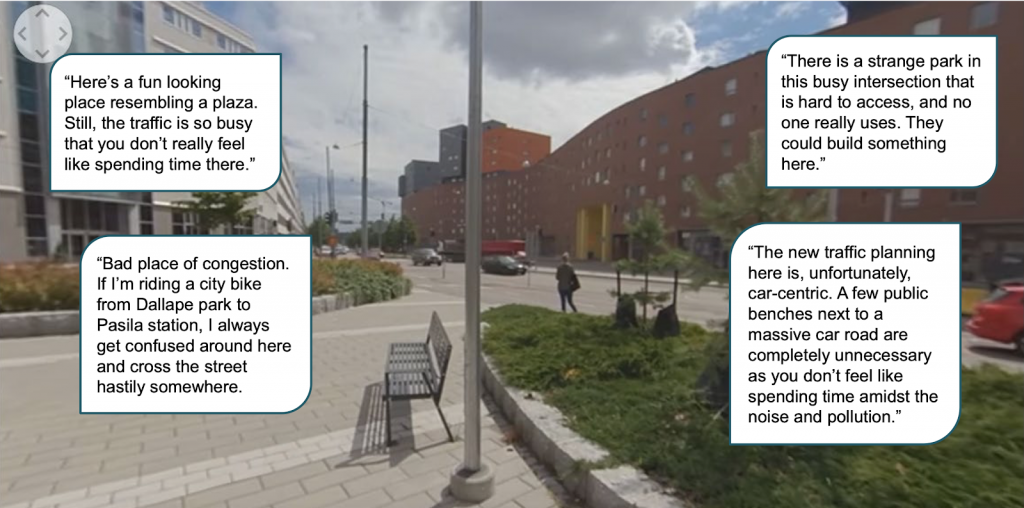

In Helsinki, 360° videos filmed at the planning site were used to visualise the existing urban structure when presenting the Teollisuuskatu outline plan to the public. The videos included voice-over narrations, with citizen comments about the urban space previously collected via online questionnaires. These illustrated the variety of personal spatial experiences, and how planning needs to balance diverse perspectives.

The medium also suits bringing future scenarios or plans into discussion. The planning team in Cēsis spurred public idea gathering by sketching potential uses for the site on top of the photos from the selected spots on the planning area. The hand-drawn sketches were deliberately tentative-looking to allow space for co-ideation, without becoming mentally too limited by the first set of ideas.

As an example of presenting a more developed plan, the municipality of Viimsi commissioned seven 360° views from the 3D visualisation of new Viimsi Main Street vision, which allowed locals to take a look around how the plan would look when realised.

Pursuing high-resolution planning communication with 3D virtual environments

Virtual environments allow more room for designing the user experience and visualising data. Everything digitally created, the developers have full control over what to include in the visuals presented. Simultaneously, the creation of those visualisations becomes more work-consuming and as it stands now, it can be difficult to create 3D models of natural environments and nature objects with high quality. Improvement of the 3D city models available and increase of other ready-made assets could ease this in the coming years. The increased control over contents calls for careful ethical considerations on the data sources and their visual representation.

Augmented Urbans primarily utilised virtual reality (VR) tools as part of participatory events. In this public setting, many were apprehensive of using the VR headset, due to the headset obstructing the view of real surroundings, fear of looking silly, the gear messing up the hair or lacking hygiene. For this, some of the tested tools had an alternative mode with mouse and keypad controls while viewed on-screen. In light of the global health crisis, the importance of sanitation has only increased, and VR headsets in public use need careful maintenance and cleansing e. g. by utilising the UV-C technology in disinfecting them.

Nevertheless, VR opens up opportunities not possible with more traditional media, such as visualising invisible factors in the urban environment. As compared to regular architectural visualisations, VR immerses the viewer into the planned space offering a more vivid perception of how it will look and feel when implemented. Bruno XR, a virtual experience developed for receiving public’s inputs on a street plan in Helsinki, allows walking (or teleporting) freely on the square while comparing the proposed plan to both the previously approved one, and the current state in different seasons, in all weathers, and times of the day. The participants could also give feedback by taking up to six snapshots within VR experience, and then annotating each of them with a short tweet-length textual note.

The conducted user study suggests that people found the Bruno XR application useful in understanding the plan. The commenting feature requires further development. While planners appreciated each comment having an accompanying image, the users found it inconvenient to first take snapshots and later add comments to them. For example, voice-recording comments could be more practical when the speech recognition applications develop to work reliably, also with more rare languages such as Finnish, Estonian or Latvian.

Another identified development point concerns the complexity of the functions. With its multiple features, the Bruno XR requires a 10–15 minute VR tutorial and a personal guide for each participant throughout the experience. This significantly limits the number of potential users and citizen inputs, thus increasing its overall cost as a participatory tool. As VR is becoming more mainstream and familiar to users, some of these obstacles may disappear, but the features and functions included in the application should be carefully prioritised and curated according to the intended use.

Some secondary features can also run on automation without user control, thus simplifying the user interface. For example, for the planning architect, the ability to control environmental factors like weather and seasons can be essential e. g. for studying the lighting solutions. For citizens, however, extensive controls seem to act as a distraction from the proposed city plans. For them, an automated cycle of changing weather could already illustrate how spatial design works in different conditions.

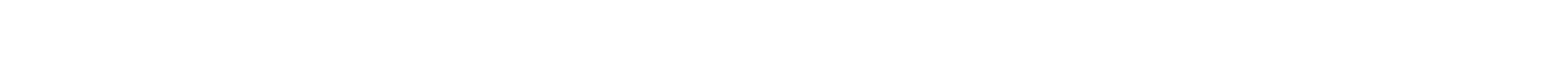

The VR prototype UrbanSphere, developed within the Stockholm case study, sets out to show how nature benefits the city. Set at the playground and pre-school Kulan, located in Skärholmen, a rapidly developing district of Stockholm, the prototype provides information on how the design of both the natural and built-up features at a site can increase or decrease the capacity to mitigate the local effects of climate change.

UrbanSphere specifically presents four functions that are key for the site’s capacity to adapt and how humans experience the site: biodiversity, temperature regulation, water absorption, and air quality. The VR experience visualises these largely invisible functions and allows participants to choose between different design options before being presented with an estimated future scenario based on those choices.

Adding information to existing urban spaces with on-site augmentation

The augmented reality (AR) adds content layers to existing reality and enables the presentation of future developments on-site. Two Augmented Urbans local actions utilised AR within their integrated planning and management processes.

In Tallinn, the city planners use an AR application to present the Pollinator Highway concept and solution for the new park area to local stakeholders. The app aims to visualise the main development ideas and spread knowledge of urban nature. It draws attention toward pollinating insects: bumblebees, bees, butterflies often unnoticed in everyday urban life but critically important to our ecosystem. The murals painted on garage walls in the planning site act as markers that activate 3D content projected into outdoor space. Compared to traditional 2D drawings, citizens get a glimpse of the future on-site, well before the long-term city plans became reality.

The user study conducted suggests that the application helped people to understand the planning vision and spurred their thoughts and ideas of the practical solution. The on-site setting also causes limitations. An example of that is seasonality—with heavy rain or sub-freezing temperatures people are less inclined to use their phones outdoors to view the plans or participate in city planning activities.

The app facilitates reaching new target groups; the playful approach can attract youth, and reduce the distance between municipality and residents, increasing the accessibility of development information. However, it excludes e. g. people with older smartphones. Currently, the app with animated 3D contents also poses a notable financial investment. Yet, it has potential to become less expensive as the technology and pre-existing 3D assets develop fast.

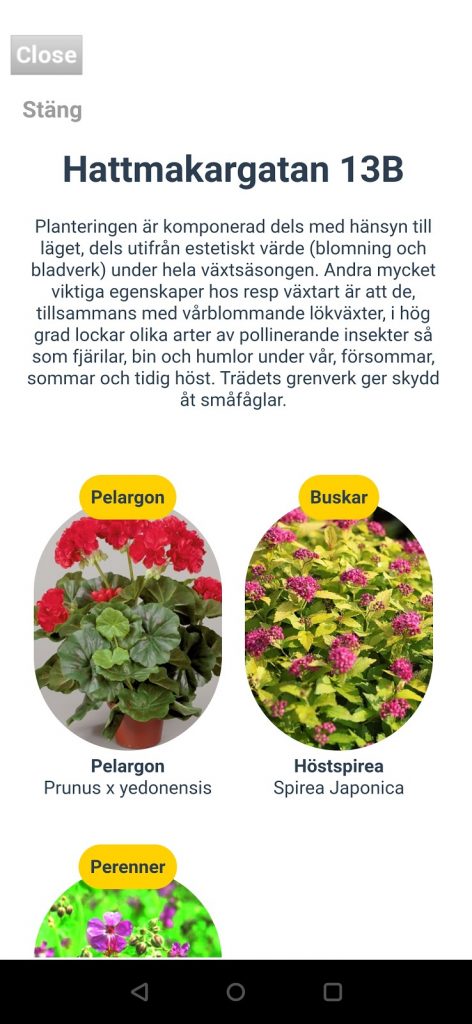

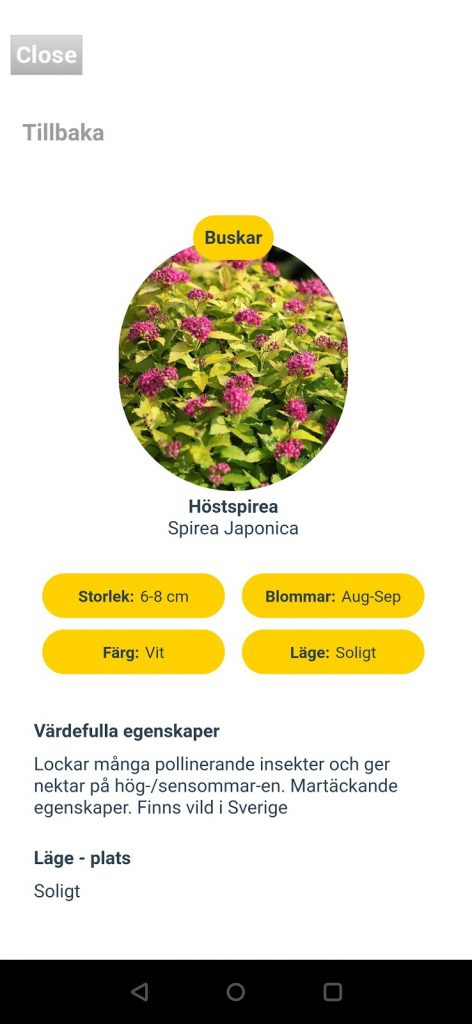

In the town of Gävle, the on-site AR focuses on guiding how to maintain and care for a more diverse green infrastructure. The project team identified the lack of knowledge to manage sites as one of the main barriers to enhancing biodiversity and ecosystems in the neighbourhoods. The developed app prototype adds information about plants, their characteristics, how they contribute to biodiversity on Gavlegårdarna’s yards.

The project team in the Riga region used Google Lens as a tool for exploring the natural habitat, identifying plants on the local case site and documenting biodiversity. As part of a planning event, the local stakeholders engaged in mapping the biodiversity on Krūmiņsala island, which increased their awareness and appreciation of the unique nature values on-site and sparked idea generation for future use, for example, using a similar approach for students’ field studies.

Building blocks for digital twins?

Extended reality applications have the potential to provide an interface to present urban data and facilitate stakeholder participation. However, they only represent a small segment in the digitalisation of the urban planning processes. The long-term feasibility of these applications depends on how well they are connected to a broader framework of initiatives e. g. the digital twins. Following articles in this chapter continue exploring these thematics further.