While there are several indicators, tools and frameworks that aim to measure or analyse the resilience and sustainability of a given system (e.g TRF, 2014; Barkham et al., 2014; Gawler & Tiwari, 2014; Khazai et al., 2015, Arcadis, 2015; OECD, 2014), the applicability of many of these methods is still contested, and both conceptual and methodological challenges persist (Sturgess, 2016). This also means that the measurement of resilience can be considered a rapidly developing field both in research and practice (Bahadur et al., 2015; Winderl, 2014).

When it comes to urban resilience, part of the problem lies in the fact that in many parts of the world urban processes are poorly documented, measured and understood, thus leading to uneven quality and distribution of data. Consequently, decision makers struggle to make informed choices about resilience interventions (Sturgess, 2016) and the capacity to develop effective urban policies is undermined (Muhammad, 2001). Many of the existing tools that focus on urban resilience are designed for a global scale and are mostly research-based, making it difficult to apply them in the local planning process. As many of these tools are essentially forms (e.g. TRF, 2014; UNISDR, 2014), there are various challenges such as understanding the specific scientific background and unfamiliar terminology. The process of filling out the documents is often also time-consuming and complex – all of which may require specialist facilitation that is not always at hand for those involved in the planning process.

Despite the fact that many planners are familiar with the more general concept of sustainability, applying it into a planning process is not always viewed as an automatic or easy task. Resilience as a concept is often less familiar to planners, making it even more difficult for them to apply the concept in practice.

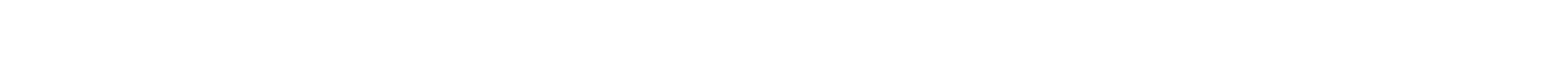

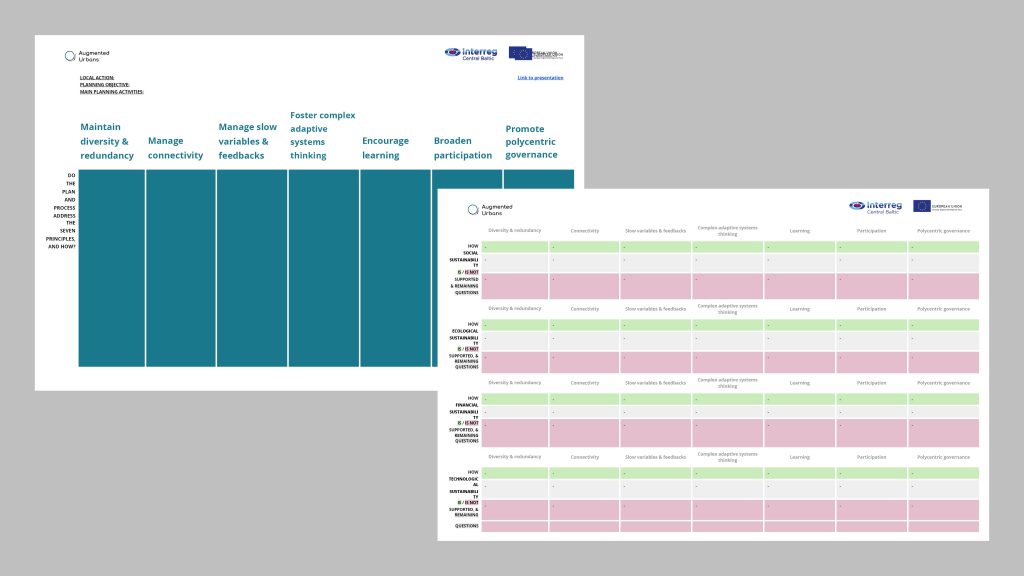

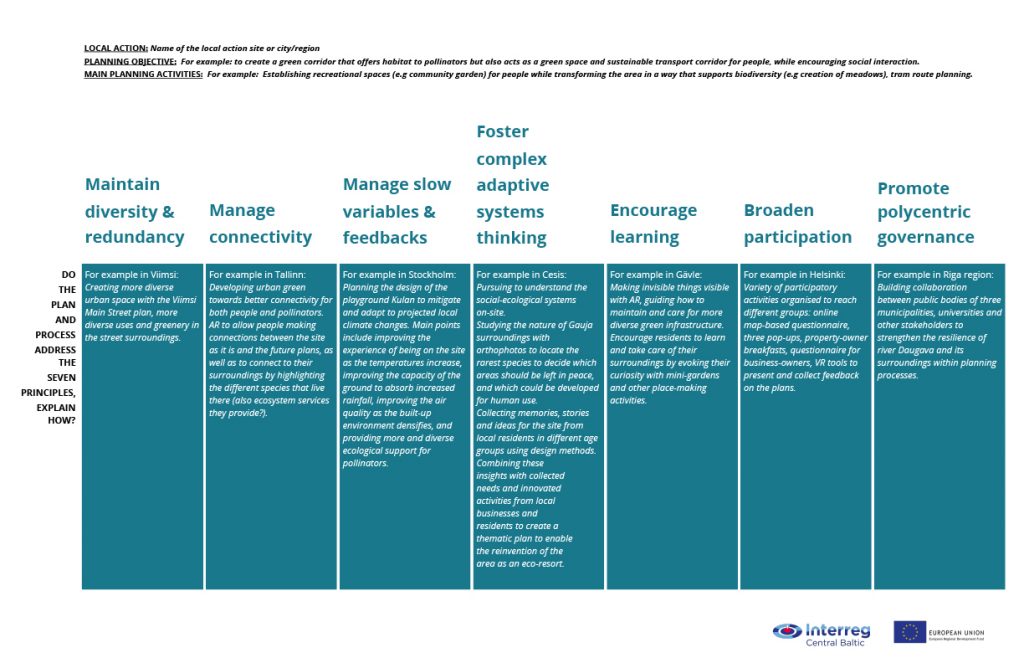

During this project a Matrix of Indicators (MoI) was developed. It aims to make the concept of resilience more comprehensible and applicable to planners. It does this by using two main steps. Firstly, the resilience principles and concept of sustainability are introduced to planners. These seven resilience principles (Table 1) are considered crucial for building resilience in social-ecological systems (Biggs et al., 2015). The second step is to discuss how these principles can be applied. The two concepts are used together to enhance the planner’s ability to understand ways of steering the process towards resilience and achieving the overall goal of sustainability. The MoI supports analytical thinking by asking planners to identify how each resilience principle is addressed in the current plan. Secondly, various sustainability sectors are analysed, applying an integrated approach. This two-step process acts as a thinking aid that guides planners through the process of resilience thinking at the level of their Local Actions or any future projects while considering the various dimensions of sustainability.

The Matrix of Indicators was developed as a tool for urban planners to identify resilience and sustainability values in proposed plans and to evaluate (existing) plans.

The rationale that underpins the Matrix of Indicators is that resilience and sustainability are interlinked yet distinct concepts, linking their interpretations to their respective local context.

Creation process of the Matrix of Indicators

The creation process of the Matrix of Indicators began by applying the City Resilience Framework (TRF, 2015) on the Local Action case studies. It was determined that this framework has the capacity to capture particularities and complexities in different urban contexts. However, it was too complicated and time-consuming for the various groups of participants in this project to use. These findings pointed out that while many cities have the will to understand and operationalise resilience principles, which could theoretically lead to the management of the inherent complexities, using the commonly available tools in practice does not always lead to the expected outcomes and using such tools can also discourage the application of these principles.

Throughout the development process of the MoI, the Local Action teams went through a number exercises to explore the meaning of resilience and sustainability in relation to their project areas and tried to understand in which ways their projects aligned with the resilience principles and sustainability dimensions. These exercises aimed to map out the social-ecological systems, including the connections between ecological, financial, social and technological sustainability dimensions.

Several intermediate versions of the MoI were created during the process, including ones that viewed the Local Action sites through the concept of ecosystem services, resilience challenges at various timeframes, resilience indicators, governance and ecosystem mapping, also system and flow mapping. Also the potential ability of the MoI to be used as an assessment tool was explored. One of the main challenges throughout the development process of the MoI was to simplify both the terminology and complexity of the concept without losing the main goal. Using examples (See example of the filled-out MoI) made it easier to translate what complex adaptive thinking means in the planning context.

The MoI workshop held in October 2020 on the Zoom platform was based on the penultimate version of the MoI where Local Action projects were analysed through the seven resilience principles (Biggs et al., 2012) that formed a matrix across the four dimensions of sustainability (social, ecological, financial, technological). The workshop began with a short lecture on the resilience concept. Completing the MoI began by filling out the planning objective and giving a brief summary of the main planning activities. Regarding each of the seven resilience principles, the users were asked to answer “Do the plan and process address the principle and how?” and this part of the MoI was filled out as a part of group work based on their Local Actions. After that, the sustainability dimensions were briefly explained, followed by another round of group work based on the projects. Facilitation was provided throughout the process but rather than instructing them on what to write directly, the facilitators tried to guide the teams through the matrix by helpful questions to raise discussion. Feedback was gathered throughout the process and in between workshop sections in the general discussion engaging all participants.

The outcomes of the workshop were encouraging, yet pointed out some of the aspects that still needed to be addressed. The tool demonstrated clearly how the planners thought, and what they considered relevant and irrelevant in the given context. Different strategies of filling it out were noted, and these seemed to depend greatly on the background of the people filling them out: some, for example, had a strong policy emphasis, others focused more on the aspects they understood best (e.g social and ecological aspects versus technological and financial). While it was not required to fill out each table cell, many felt that if they did not complete the whole table, they had either not grasped the concepts fully or felt their projects didn’t cover those aspects. It was at times challenging for the participants to find a single specific cell in which to write their ideas, instead preferring to place that same text into several cells, especially when already having completed the resilience part and then continuing further to the sustainability dimensions.

Based on the input from the workshop, the final version of the MoI was compiled where the sustainability section was simplified even further. The final version of the MoI consists of the seven resilience principles where the users are asked “Do the plan and process address the seven principles and how?” (see image below with an example of the filled out version of the MoI). Secondly, users are asked to fill out the four sustainability dimensions by describing the following aspects: 1) factors & planning actions that support sustainability, 2) unsustainable factors and 3) remaining questions. By pointing out unsustainable factors, it is possible to map out aspects that still need to be addressed in the future. This is also helpful when using the MoI with several plans, and if similar aspects keep coming up, the key challenges can be identified, helping to pinpoint where action is most needed. The remaining questions help to determine specific knowledge gaps that can be covered either by training programmes or individual learning or addressed as both theoretical and practical research questions if no concrete answers exist yet. The current version of the MoI does not enable evaluation or direct comparison to other sites, as different sites may choose to emphasise incomparable elements. Yet it does make it possible to compare different versions of the plan at the same site to monitor potential improvement.

Using the Matrix of Indicators

The MoI can be used as a tool to record and follow the planning process by applying resilience thinking and considering different sustainability dimensions. It is a thinking aid, something which planners can return to over time, and it has shown to be especially useful to those who prefer to structure their working process as if following a checklist. Unlike a checklist, however, the MoI enables more clearly to identify the linkages between different resilience principles and sustainability dimensions. The MoI can be used to elicit information and the details of a planning process and compare case sites by finding common elements and synergies and identifying common challenges, which may also lead to the possibility of adapting successful solutions which have worked elsewhere.

The MoI, as any framework, has potential to be developed further. However, here the most vital aspect to keep in mind is the end goal – whether that is to assess and compare the results to different projects or rather the main goal of facilitating a thinking process. The former can be achieved by using specific but easily accessible and available indicators together with a more qualitative content. The latter also depends greatly on the timeline – with time, it is likely that more and more planners are better acquainted with both resilience and sustainability concepts, hence requiring less specialist facilitation. This would help to specify some parts of the MoI to enable even more precise thinking. For example, instead of just observing community engagement as a broad concept, the specific ways and methods used for that could be analysed.

The fillable pdf of the matrix can be downloaded here.

References

- Arcadis. (2015). Sustainable cities index 2015. https://s3.amazonaws.com/arcadis-whitepaper/arcadis-sustainable-cities-index-report.pdf

- Bahadur, A.V., Wilkinson, E., & Tanner, T.M. (2015). Measuring resilience: an analytical review. ODI Working Paper. Overseas Development institute.

- Barkham, R., Brown, K., Parpa, C., Breen, C., Carver, S., & Hooton, C. (2014). Resilient cities: A Grosvenor research report. Grosvenor.

- Biggs, R., Schlüter, M., Biggs, D., Bohensky, E.L., Burnsilver, S., Cundill, G., Dakos, V., Daw, T.M., Evans, L.S., Kotschy, K., Leitch, A.M., Meek, C., Quinlan, A., Raudsepp-Hearne, C., Robards, M.D., Schoon, M., Schultz, L., & West, C.P. (2012). Towards principles for enhancing the resilience of ecosystem services. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 37, 421-448.

- Biggs, R., Schlüter, M., & Schoon, M. (Eds.). (2015). Principles for Building Resilience: Sustaining Ecosystem Services in Social-Ecological Systems. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781316014240

- Gawler, S., & Tiwari, S. (2014). Building urban climate change resilience: A toolkit for local governments (ICLEI ACCCRN Process). ICLEI South Asia.

- Khazai, B., Bendimerad, F., Cardona, O. D., Carreno, M. L., Barbat, A. H., & Buton, C. G. (2015). A guide to measuring urban risk resilience: Principles, tools and practice of urban indicators. Earthquakes and Megacities Initiative.

- Muhammad, Z.B. (2001). Development of Urban Indicators: A Malaysian Initiative. In J. J. Pereira & I. Komoo (Eds.) Geoindicators for Sustainable Development (pp. 17-32). Institute for Environment and Development: Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia.

- OECD. (2014). Guidelines for resilience systems analysis. OECD Publishing.

- Sturgess, P. (2016). Measuring resilience (Thematic Summary). https://www.gov.uk/dfid-research-outputs/measuring-resilience

- TRF. (2014). City resilience index: City resilience framework. The Rockefeller Foundation andARUP https://www.rockefellerfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/100RC-City-Resilience-Framework.pdf

- UNISDR. (2014). Disaster resilience scorecard for cities. United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction.

- Winderl, T. (2014). Disaster Resilience Measurements: Stocktaking of ongoing efforts in developing systems for measuring resilience. United Nations Development Programme. http://www.preventionweb.net/files/37916_ disasterresiliencemeasurementsundpt.pdf